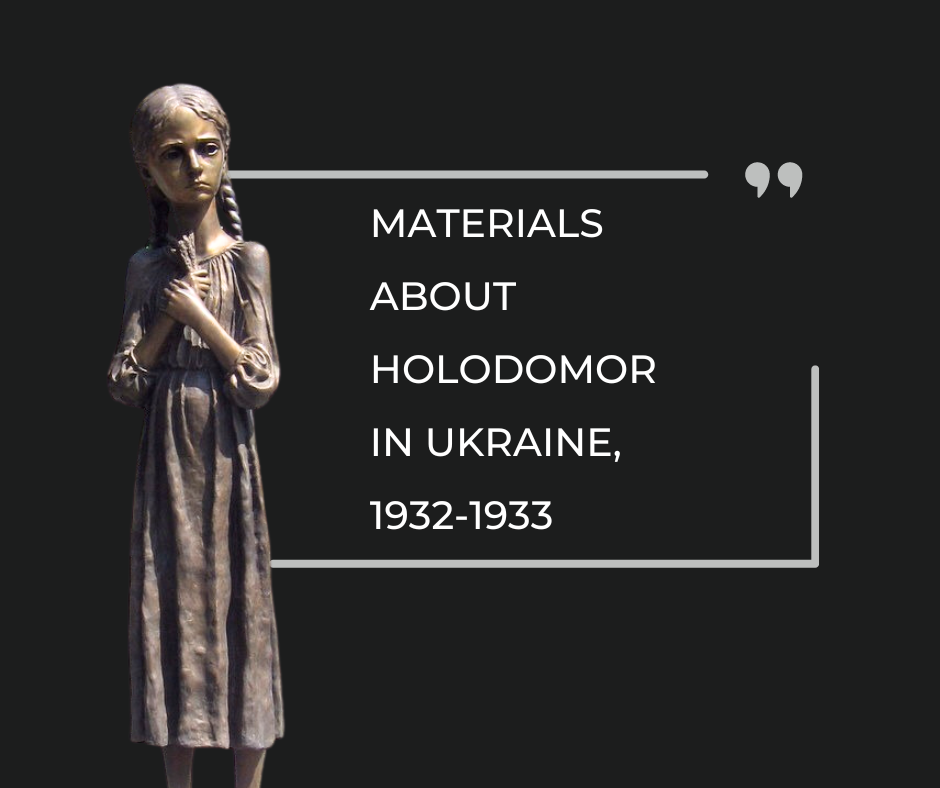

On November 21, the UNWLA welcomed Dr. Emily Channel-Justice, the Director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine Program at the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University, and Dr. Kristina Hook, Assistant Professor of Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University’s School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development. Both anthropologists and experts in Ukraine, they discussed Dr. Hooks’s research of the Holodomor 1923-1933 and how it fits in the context of the current Russian aggression against Ukraine. The Ukrainian National Women’s League of America publishes the conversation with a full transcript.

Natalie Pawlenko: Welcome everyone, and thank you for joining us for this incredibly important conversation between two scholars who have spent a great deal of time thinking and writing about these issues. Allow me to introduce Dr. Emily Channel-Justice who is the Director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine Program at the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. She is a sociocultural anthropologist, and she first started learning the Ukrainian language and carrying out research in Ukraine in 2012. She pursued research on political activism, social movements among students and feminists during the 2013-2014 Euromaidan mobilizations. You’ll be interested to know that she is the author of Without the State: Self-Organization and Political Activism in Ukraine published by University of Toronto this year.

And our other guest this evening is Dr. Kristina Hook, who is an Assistant Professor of Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University’s School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development, and a specialist in Ukraine and Russia. Her expertise includes genocide, and mass atrocity prevention. As an anthropologist, Kristina began conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Ukraine in 2015, analyzing archival records of the Holodomor and the historical memory of this event for Ukrainians today prior to her time at the Department of State as a policy advisor for conflict stabilization and in leadership roles with several non-governmental organizations. Dr. Hook wrote an article for the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America titled The Holodomor as Genocide, A Social Science Approach to Understanding Past and Present Violence in Ukraine. This article appears in our November, this month’s issue, which is dedicated to the memory of the Holodomor.

We are very honored to have both Dr.Channel-Justice and Dr. Hook with us today as we all this month honor the memory of those who perished 90 years ago during the Holodomor. We look to see and hear what parallels might be drawn to what is currently unfolding in Ukraine. So without further ado, I present to you Doctors Channel-Justice and Dr. Hook.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Thank you so much for the invitation. Thank you, Kristina, for joining me for this important discussion, to all our viewers. Kristina, I’ll just begin by asking you to maybe talk a little bit about the article that you’ve published in the journal and why it’s so important that this article comes out this month.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thank you so much, Emily. I’ve really been looking forward to this conversation. Whenever I give these presentations, I think this particular venue is really crystal clear why this topic matters. We’re so grateful for the opportunity to have the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America give us the opportunity for this discussion. And we know that by doing so, they’re gathering also members of the Ukrainian community and the audience that’s here with us today. And for all of my talks, those are some of the most meaningful, because I often have survivors or survivors’ descendants and these talks… these talks are really important for just keeping that memory alive. We are talking about a story that was illegal for many years. For making sure that there isn’t any kind of impunity that Stalin can get away with, as well as that theme that we’re having about the current escalation under Putin and conversations of getting away or impunity with prior acts of violence.

I appreciate the introduction because it gets around a couple different aspects of my background that this case is also really helpful for us in seeking to really take practical steps towards the genocide mantra that we all share of “never again.” It’s, easy to say even with a lot of heartfelt conviction, but how do we enact something like “never again”? How are we able to anticipate where genocide might happen, or once that’s happened, what steps can we take in very practical ways to stop it? And in order to do we look at a lot of historical cases.

So it was this topic that first drew me to Ukraine, which is now the center of my work for the past almost eight years in a place that I know both of us have spent a lot of time and care a lot about. I was drawn there because I knew about Stalin. I knew that he was a totalitarian, I knew he was responsible for some of the worst crimes that we can speak of in the past century. But I wasn’t really sure if this case met the way that the genocide scholars like me often speak about genocide. And so I wanted to, really look at the archival records and without feeling that I would put my finger on the scale a little bit. I didn’t have a pre-ordained conclusion. So that I went and I started doing archival work.

And I’ll just mention a little bit too, if it’s all right, about questions that people have about comparative genocide research. It’s really challenging because often genocides are happening with a kind of “a whole of society effect.” So you’ll see maybe the most powerful people, the sort of direct authorizers of violence, if you will. This would be Stalin in this case, but they’re carried out by direct perpetrators, which would be included in the Holodomor, the people requisitioning grain. They’re also involved with the bureaucracy that does, let’s say, those edicts to take grain for the first time. And so it’s a big social enterprise to organize a genocide.

And it’s this real challenge because when you’re looking at even that top level of leadership, even with Stalin or other cases that I’ve worked. They’re often in at minimum and authoritarian context to control that kind of bureaucratic mechanism. And because they’re authoritarian or totalitarian, they often don’t ever feel the need to really tell their subordinates what they’re doing, who they’re targeting, and for what purpose. It’s common in our field to not really find explicit written declarations from even lead authorizers about “I am targeting this group of people for this reason.” So the way that we work, both my work in the Holodomor and then in other cases, we use what’s called in social science proxy variables. We’ve looked at, for the last 60-70 years of genocide research, we’ve looked at the Holocaust, we’ve looked at a lot of other cases. We found these indications that we expect in the record they’re getting at these deeper perpetrator motivations. That’s what I began to see when I was looking at the case of the Holodomor, all of those indicators that I was expecting to see did begin to emerge in those documents for me.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: I want to follow up a little bit on this methodological question. We’re both anthropologists and for me anthropology is so often a contemporary discipline. It’s something that we use to look at what’s happening now and to understand… We always have to look to the past to understand our context, but it’s not always self-evident that anthropology can help us understand a particular moment in the past that’s already happened. Can you talk a little bit more about how the field of anthropology led you to this type of study and how you use anthropological methods such as ethnographic fieldwork in addition to your archival work?

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thank you so much. It’s a great question. It also shows that I wear a little bit of a split hat and on purpose. When I began this work, I was doing my doctoral dissertation at the University of Notre Dame. And so they have a joint program, which was anthropology and peace and conflict studies. It’s a pretty rigorous program in terms of you have two departments and you often can hear that interdisciplinary tension in our field exactly the types of themes that you’re talking about. And so it’s a little bit of anthropology with also a comparative genocide lens, which is very much an interdisciplinary discipline.

I’ve always found that anthropology really has something to bring to the table. And even there is this kind of growing voice within anthropology that talks about historical anthropology. So I think what it does is it begins to look at genocide, not just as a term that is so horrific that it can cause us to even wanna look away, but it invites us to look at genocides as a complex social behavior which is what anthropology’s all about. This exploration what it means to be human, even this very dark side of being human. And so my argument for my fellow anthropologists has always been that we have something to say here because genocides are really an extreme form of social behavior. And because of that, there might be commonalities that we can pull in that we also wanna keep our contextual sensitivity as anthropologists. That’s something we like to bring to the table. We like to talk very much about the details of this specific context, but my argument’s always been that genocide, for a variety of reasons, against a variety of groups with all of their rich and nuanced complexities still is a very extreme form of social behavior and we can really tease out some of those social dynamics because of that.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: I think that’s absolutely fascinating. I’ve never really thought about it this way. So for me that’s really enlightening. Let’s talk about the other side of making the choice to do this kind of research, which is the Ukraine side. You said that this case of the Holodomor brought you to Ukraine, that’s what kind of drew you there. For you, what was the process of learning how to use the archives in Ukraine for you? What language skills did you have to develop? How did you establish connections? For someone who’s not Ukrainian, who doesn’t have a background that comes from Ukraine, we both know that we’re starting from basically scratch. So can you talk a little bit about that process?

Dr. Kristina Hook: Absolutely. One of the things that I do love about anthropology too is that we just get to spend a lot of time listening. When I went there, I had Russian language skills, which is why I knew the archival work would be a first step that I could take a first step on what I knew would be a multi-year journey. The archives are in Russian and so that is an important language for understanding the world, although a lot of oral storytelling and memories are now in Ukrainian. But when I got there, one of the things that my work has really expanded from just archival research because when I got there, I was doing interviews. I wanted to hear from different people who interact in their professional roles with the topic of genocide. And I wanted to hear what the Holodomor meant to them. So what did the Holodomor story mean? If you were a civil society activist, what did the Holodomor story mean? If you were a legislator or someone working in the legal field, what does the Holodomor mean if you’re a politician or a policy maker? And what does it mean if you are an academic? And I picked those four categories because I’ve done three of them myself. And so I know that when we interact with this concept of genocide, that it can mean slightly different things just because of the professional nature of our work. Basically, everyone’s bringing something to the table, but they’re all a little bit different. So a lawyer is trying to establish that genocide can be prosecuted and the way that we speak about it can withstand legal scrutiny and hold perpetrators accountable in a court of law. A policymaker like me is really looking at how we can stop something in motion and we’re trying to figure out how we could (my previous role) how we could organize chaos really fast to make some kind of meaningful intervention, whatever that may look like in a certain context. A scholar is usually focused on either a topic, if you’re a genocide scholar, or a context like Ukraine. And is really looking at a lot of rich detail, but then how you translate all of that rich detail for policymaking. And then also civil society plays a hugely important role, especially in the Holodomor, they kept the story of Holodomor alive. And so I really wanted to speak with all of these groups and not just stay in the archives. So that also is why I started learning Ukrainian in 2015 and it is really a language that is dear to me today. Whenever I hear someone speaking Ukrainian today, I know that we’ve all had hard things happen in our circles this year. And there’s a real sense of kindred spirits, I think right now, I feel very privileged to speak Ukrainian.

I started off this long answer by saying that anthropologists get to listen. I had a host university in Kyiv, the University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy who has just been a wonderful host for my research there on several different fellowships.

But when I began to speak with these four different actors that I talked about, there was a theme that kept coming up within all of them, and the theme was.. kind of this fear that Stalin has done this in the past, that there was this Moscow of the past, and that there was a lot of concern spoken to me from 2015, which was the early day of the arm conflict beginning, that it might happen again.

This article is really just on the scholarly case for genocide, but my larger work is really on telling the story of how these four groups of actors really saw so many things coming because I expected so much more disagreement. I’ve been in these four different roles and even though we all try to work together, we just view things a little bit differently. We’re looking for slightly different evidentiary standards and so I really expected a lot of disagreement and I was finding a lot of convergence in the story that people were telling by people that were really also offering a lot of perceptive commentary about other things. And so for me, the story of the Holodomor is actually what really began to raise my concerns that the current escalation could happen but also really began to clue me in on the fact that very different people were also going to be ready to stand up. They understood the historical stakes of what it would mean. Thanks for that question.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: That’s a really excellent segue into talking about the current moment. You mentioned already that you have and you’ve written pretty extensively on this that there’s evidence that we should be calling this particular part of Russia’s intervention, invasion, attempted takeover of Ukraine, we should be calling this a genocide. I wonder if you can tell us a little bit.. this is gonna be a long question. First of all, what have you learned from your previous experience in studies of genocide that are indicating that this is in fact a genocide? Secondly, why is it important to advocate that it is in fact a genocide now while this war is ongoing? And as we’re constantly being bombarded with new information and most often new information of atrocities, what is the expectation of the response from the international community if this is in fact designated as a genocide?

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thank you. These are most important questions that I feel I answer today. So if it’s alright, I’ll just take two hours on them. No, but I do want to walk through actually all three of those parts because they’re really important.

There is a lot of disagreement even within scholars who study genocide, which is a good thing. Social science is richer by lots of debate, lots of critiques. But there have also been what we call in the social sciences these meta reviews. Scholars who have gone to all the painstaking work of reading the hundreds and hundreds of books and articles that are published on particular aspects of how genocides unfold every year. And those have been really helpful. They’ve been done in the last 15 years because they’ve pointed out that a couple things that were really important. First of all, how much disagreement we unconsciously bring to the conversation of genocide. One of the meta reviews showed that even genocide scholars (so we do this all day, every day) even genocide scholars in the major books that were published on genocide in the year 2008 when the study was done, they were all actually using the term genocide in a slightly different way. And that’s a problem just if you’re trying to stop violence in real-time, you’ve got to know what you’re looking at so you can better tailor your response. But all hope was not lost because the same meta reviews were saying like, okay, there are lots of things that the field will always disagree on just in terms of how we do the business of social science, but there’s key consensus around two main questions. And if you can answer these two main questions, then there’s really field-wide consensus, even in our interdisciplinary world, about what separates the unique social phenomenon of genocide from other forms of also severe equally heinous [violence]. One’s not morally worse than the other. We’re actually trying to stop all of them. But that can separate this unique social phenomenon of genocide. And those two questions that you wanna ask are who is targeted and for what purpose? When you’re asking who is targeted… we work a lot of terrible heinous cases, but some cases, for example, teenage boys are often singled out because they’re viewed as future combatants. They’re viewed as a real threat by perpetrators of violence. But that doesn’t exactly fit the kind of perpetrator ideology of genocide where destruction of the entire group is being pursued with a great deal of effort.

For genocides, we expect to see more of what we call in technical speak, unqualified group selection. We’re looking at men, women, children, a lot of different variety within the targeted group. And then we’re also looking at ways that we can tease out what is destructive violence from what is severely repressive violence. And again, these are both heinous, but they are different logics. Repressive violence, if you’re the perpetrator, you’re seeking to harm the victim group, you’re seeking to batter it. You might be seeking to enslave it, but you want to keep those people alive but in a subservient, cowed, subdued role. With destructive violence, you’re seeking to eradicate those people’s core identity. And that can happen as a segue through killing or through what we’re seeing today, which is forced Russification, but it’s really a destructive logic.

And that’s something that I saw in the Holodomor. It’s actually quite clear in the documents to me when we were looking at these ways (that I use for all of the genocide cases I work on) at teasing out this destructive violence and teasing out this victim selection. We can see both of them in the Holodomor. So that’s really what we look at.

I think your second question, I might answer them in a different order but the logics of violence for genocide and for these other heinous forms of mass killing are just really different. Knowing from my policy experience, perpetrator logics – the interventions have to be tailored to where that perpetrator’s at. It’s actually the hardest, I think, to stop genocides because people are very ideologically motivated. This is a psychological commitment to wipe out a group of people. So they’re willing to take greater risks, they’ll go to greater inconveniences. They’ll have this kind of what otherwise might be idiosyncratic behaviors. Some of them that we’ve seen that I’ll draw parallel to both the Islamic state ISIS, the case that I worked as well as what we’re seeing today is this pursuit of victims. So at ISIS, we saw them pursuing the Yazidis group up a mountain.

We also saw that in the Holodomor, where by the way, it was very significant for me when I saw in the historical documents about very careful record keeping about Soviet soldiers pursuing fleeing Ukrainian peasants, catching them, counting how many they caught and then often putting them back in their famine-ravaged villages, sealing in the villages until those people died and then, often in these same areas, bringing in resettlement campaigns for other groups. That pattern is a little different today but is still very similar. We’ve often seen evacuation caravans targeted by Russians, or you’ve seen really willful efforts at population control and pursuit of victims.

Now, that’s risky behavior. I’ve seen other cases where, you know, you just want to batter a group, scare it. It’s much easier to do something heinous, but less inconvenient, less chances that you’ll get caught, like throwing a bomb in a marketplace and just running away. So when you’re actually pursuing victims, you’re going to a much greater length and you’re really communicating there, as was the case in the Holodomor and as is the case today that it’s not just about the land, the looted possessions, both in the Holodomor and in the case of modern Ukraine. I’ve talked about pursuing these evacuation caravans. It’s not enough to just drive victims from their homes and to take their land as the gain that’s your goal, but you’re actually seem to be after the people itself. And that’s a really different logic. And that also is really challenging to stop because it’s indicating that you’re not bought off by just stealing everyone’s life savings. And so that’s really why it matters today. So I have written other articles too on what’s happening today and, trying to walk people through the kind of different roles that people play.

I talked about that previously. In the Holodomor, Stalin was a key authorizer. There was even a Kyiv court that looked at the key architects of the Holodomor and of course found them guilty, a credible case there. But those people would be the authorizers. What about also this constellation of bureaucracies and military structures that are also carrying it out?

You’ve got to go into the situation with that awareness, because whether it’s Stalin or Putin, I’m arguing always that this is a really distinctive social phenomenon. When these leaders unleash these social dynamics, that genie can’t really be easily put in the bottle even by totalitarian authoritarian leaders. You see a of moral calculus changing in society around where pursuing victims is not just an unfortunate thing that you have to do.

So in the Holodomor where it might be “it’s unfortunate, but they’re resisting collectivization,” or today it might be, “it’s unfortunate,” as Russia was claiming falsely, “we’re not trying to target civilians.” But really it changes from this unfortunate ethical behavior to something that’s actively beneficial. For example, in Holodomor it would be “we have to do this, it’s a good thing for the Soviet Union,” or today it would be “we have to do this, this is for our Russian grandchildren,” I’ve seen language like that. To sum up that very long answer, we do look for these distinctive patterns of who is targeted and for what purpose, for a destructive intent that does lead to a really different logic.

I also want crimes against humanity and genocide to be prosecuted in a court of law. They’re all heinous. They all deserve their day in court and their justice. But I’ve argued if we had been able to stop the Holodomor then, and as we’re currently trying to stop Russia’s actions today, we have to really tailor it to not what we wish the case to be, but what we see perpetrator and societal dynamics around it shaping up to be.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: That’s so helpful. Those parallels, they’re heart wrenching to listen to you make those connections, but I think it’s really helpful for us to really understand the scope of what we’re dealing with right now. So I have two questions that came out of that response.

The first one has to do with documentation because of course, one of the things that we know about Holodomor is that the evidence was repressed as much as possible by the Soviet authorities so that no one would learn about those crimes. I’d be curious to hear you reflect a little bit on the different kinds of documentation that help you find the evidence for your research about the Holodomor versus the kinds of documentation that we have now. Of course, it’s a completely different landscape in terms of how we find evidence and what that looks like but the parallels of the kinds of practices are so striking. It’s just we’re seeing the same thing be repeated, it’s just that we can visualize it in a really different way. If you’ve thought much about that, I’d love to hear your take on it.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thanks. There are a few outstanding questions for me. I feel like we really have enough to have a clear understanding of it as genocide, but there are silences in the historical record and there’s a lot of brilliant scholars. I have a long list of people that I would love to introduce who also work on the Holodomor and specifically talk about these silences and the historical record, talk about all the eyewitness accounts that were suppressed. The ones that did survive are very important and precious to us in the research community.

Now, we did have decades later a U.S. Congressional Commission led by James Mace that also led to capturing a lot of those stories, which this was in the 1980s, but it was very important just for the age range of the Holodomor survivors. And I’ve been privileged also to interview people who were the Holodomor survivors. This is my sort of standing invitation in the field. If there’s ever a Holodomor survivor that wants to share their stories, we can make that happen. It’s very important to collect all these stories. When I was looking at this case, I really was very interested in perpetrator dynamics, and so we had enough for that.

Now when I wrote my first master’s thesis on the Holocaust, and there is more bureaucratic documentation for the Holocaust, meticulous record keepers down to the mid-level groups. There have been these massive volumes on Holocaust bureaucratic mechanisms, which have been really helpful for me in the work that I do and that we don’t always have with the Holodomor. I’m not convinced that they’re not there. They’re just sometimes in Russian archives, which are no longer possible. Actually in the 1990s, a lot of those documents that were significant for understanding Stalin and his inner circle’s genocidal intent we actually published from Russian archives, published in books. Even though the original records are not always accessible, we have more than some people think. And in Ukraine, there were different waves of declassification of these Soviet records. There were several significant ones since I began my work and even after the Orange Revolution even more recently. So we really have enough to look at those key architects of genocide. That doesn’t always tell us everything we want to know. I always want to know more about the victims and people. Doing the ethnographic work I did, which was talking with a lot of people from those professional fields and people who were the descendants, it’s just stories of family memories. Every family memory makes me want to go and collect a hundred more because they’re so important.

And it was illegal to talk about those stories but people knew. People weren’t always able to tell their whole family. So I would learn if people who later found out they’d had siblings who had been killed under Holodomor, but their parents didn’t tell them for reasons that they might let those dark secrets slip and then endanger the family. But many of those stories were kept. Now for the records with Stalin, we’ve got enough. Sometimes during time in the field people say “do we have enough to even make a definitive conclusion?” So I really want to say strongly that yes, I believe we do, and I’ve published research on it. We can see this clear overlap for Stalin in his inner circles, what they were thinking, what they were planning very much in keeping with the type of documentation that we’ve also had for other cases I’ve worked on. So I don’t think that’s a serious concern for genocidal intent.

Now you asked me also about documentation and what’s going on now and just the role of the technology age is very much shaping our understanding every day. I think we’re all in social media, checking in with our Ukrainian friends and colleagues, looking at all of these videos and social media posts. Our planning now is for prosecution. I’m involved in several efforts for that. This is a comment about technology, not about how much genocidal incident was present. We have talked in my professional circles about the given advance of technology. For the Nurenberg trial, we had hundreds of cases for legal documentation and legal discovery for the court process of prosecuting the Holocaust against Jewish people and others by the Nazis. For Bosnia we had thousands. And then for Ukraine, we’re really looking at possibly millions of records because there’s so much documentation. There is this growth of open-source intelligence, people online are actually able to do some work that is of great service to investigators. So we are also thinking a lot about that, but a few of us are trying to approach this as technology helping us.

This is like another hat that I won’t get too sidetracked on, but I often work with computer scientists on research projects related to Ukraine. My computer knowledge remains pretty rudimentary, but we’re on these interdisciplinary teams because they’re able to talk through how we can use artificial intelligence for sorting different things, for helping get through the data cleaning or data organization so that we can then, with our human specialization, look at the evidence in front of us. For a long time, it was about data collection. And even in the Holodomor, we might talk about that because it was suppressed. The records even in Ukraine were not always declassified. So it was really a question of data collection. What’s going on now? It is collection always, but it’s also about organizing that data because there’s so much of it coming that the metaphor we use is like trying to fill this small porcelain teacup with a fire hose. So how do you do it in such a way that you can make sure that no one’s story is lost and that everyone has their day in court?

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: You’ve given me the, perfect segue to the next question, which is about justice. What does justice look like in both of these contexts? Do you have any speculation on what we could see about holding Russia and Russian actors who have perpetrated both of these genocides on Ukraine accountable?

Dr. Kristina Hook: I often think about this. I think about how much I had to learn. I was always very interested in the Soviet Union and obviously the great evils that were done, always really impressed with the stories of dissidents that would come out from the Soviet Union. But I still had a lot to learn about the Holodomor before I started living in working in Ukraine.

So I love to see it more in our curriculum and our education. I think that’s important and I often wonder (we’ve also had these conversations since the war began) about how was the largest country in Europe with a huge population of, let’s say, 44 million people missing from people’s mental map of Europe? How did that happen? And I think that the Holodomor and the repression of it was part of that story. I think it did lead to these questions of impunity that we’re having today. These questions are from a lot of us who are trying to raise alarm about concerns that we saw, the rhetoric that we’ve seen for the past eight years of this armed conflict that didn’t just begin in February. How was it so hard to make this case? Why did we have to answer questions over and over again about this being a civil war, which it wasn’t? It was nice to see the court case come out of the Netherlands about MH-17, just because it clearly talks about the role of the regular Russian military forces.

I think the Holodomor is a part of that. It’s important for honoring the victims. It’s important for me as a kind of technical specialist to do everything I can to support and participate in commemoration, education, and then also in my small way to try to honor the victims by saying that I see your story, I know it happened, and I’ll do everything I can to both help stop what’s happening in Ukraine today, as well as help people in other locations that are experiencing violence.

We’ve also seen, incredible solidarity of Ukraine with countries that are experiencing protests like Iran. So we are trying also to talk about this case of the Holodomor in solidarity with others. It’s also important for the story of the Holodomor where I was really interested in how the U.S. Congressional Commission happened in the 1980s. In my dissertation, I wrote about this massive protest that was held in front of the Soviet Embassy in the 1980s by not just Ukrainian Americans, but with a significant role of Jewish Americans, their solidarity played a role as victims of another major European genocide. Solidarity, education, stopping genocides, understanding these social dynamics, and then again, this question of impunity. Why was it so hard for Ukrainian voices to break through? Why was Ukraine missing from people’s mental maps?

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: I completely agree with all of that. Thank you for articulating it so nicely. I’m going to ask one more question and that has to do with the question of starvation. We’ve seen already food resources being politicized, being used as a political bargaining chip by Putin. You’ve written some things that talk about how that echoes some of the tactics used during the Holodomor. But for those people in the audience who haven’t read everything that you’ve written about this, maybe you can talk a little bit about the role of starvation and the potential food crisis.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Sure. It’s really a way of using food as population control and population targeting. Sometimes there are some questions about the Holodomor that people have and one of them is “does willful starvation count?” Sometimes people think about genocide is maybe shooting deaths or Rwanda’s hacking deaths with machetes or, of course, the horrific gas chambers in the Holocaust. But yes, starvation is certainly a part of that. Whether Stalin orchestrated Holodomor from the very first day or whether he capitalized on other things to willfully intentionally accelerate it, really none of those on their own are an issue for conversations of genocide because comparative genocide studies are really focused on the intent of violence, which is carried out in different contexts through different methods of violence. I’ve had people read some of my dissertation or parts of my book, and even colleagues in the field said they had to put some of these stories down because they were crying.

The role of starvation, the slow dehumanizing death that results in both psychological changes for people as well as physical changes, that results in really other very extreme antisocial behaviors like cannibalism, just because it’s also precipitated with a lot of just psychological breaks, it really plays a role in collapsing the social order. So things that our societies depend on, things that were really well developed in Ukraine’s traditional agricultural society at the time, where were things like values of sharing. So if you have these people working together on farms, working together to build barns, all of these social practices in that type of economy that are structured around sharing, you have starvation, Suddenly it’s every man for themselves, and it ruptures those things that have made societies thrive. And so the role of starvation, it’s just a terrible, way to die because it’s very slow. And I think that it did play a role in why the story was very challenging to talk about for a long time.

There was of course the fear because of Stalin, because of this top-down pressure, these treason laws where it wasn’t just the person who told some dangerous secret that could be targeted, but their entire family, even if they had no prior knowledge. But again, also just the kind of stories that people have that I’ve collected in my work. They’re very painful and very difficult to talk about. And I think some of that might also be why certainly these memories were kept alive in families, but there are many people I talked to that found out later, or their grandparents or parents told them parts of the story. I have a few Ukrainian colleagues who are historians that found a little bit more out from the historical records than they even learned in their families because [the memories] were so painful with all of this dehumanization.

This role of methods of violence is most important. But I think the slow nature of dehumanization through starvation played a real role in the societal traumas, in the reluctance of people to feel safe talking about this. I think even in the early years of Ukrainian independence, something that I was really interested in and that I talk about my wider work about, was people who didn’t even feel safe talking about this.

I interviewed former president Victor Yuschenko, for example, he did a lot of [work] with social memory. And he would tell me he was the president and he would meet elderly women who were Holodomor survivors. And he would say, “will you please write down your stories? I have my secretaries here. They can sit down with you and record your stories.” And they would still, even during his presidency, speak with a presidential figure assuring them that it was safe to talk about the topic, they were still scared to talk about it. And he said, “I think some people only tell those stories in their prayers.” I think that the dehumanization has also played a role in some of the fear associated with talking about it.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Thank you. That was an incredible answer. We have a couple of questions from the audience. We’ll jump back into the contemporary world with a question from Roman Serbyn who wants to know what you think is Putin’s ultimate goal for his genocidal destruction of Ukraine and Ukrainians as a national and ethnic entity.

Dr. Kristina Hook: It’s a hard question because I don’t like the answer I see. I think what is going on today, what I’m observing in contemporary Ukraine, is a genocide orchestrated by Putin, but as we know, carried out by hundreds of thousands of other Russian perpetrators ranging from direct perpetrators to soldiers who are doing this horrific violence. All of the people working in occupation and deportation bureaucracies. I will also mention that the records of forced deportation and taking people’s passports, giving them new passports, was something that played a very important role in the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia. The paper trail that creates, I’m expecting it to be very important for legal prosecution. Then we have people who are working on the “children’s services”. I really can’t say that without quotation marks because you know that it is clear from Article 2, section E of the UN Genocide Convention that the forcible transfer of children from one group to another is a clear and legally recognized marker of genocide. So all of these people are playing a role.

What I’m seeing today fits the case of genocide being waged against the Ukrainian national group. Because I think one thing that’s happened, something we really see from your area of expertise, Emily, is the role of people of different ethnic heritages in Ukraine today. Today we have the day of Dignity and Freedom, which was started by someone who’s obviously a proud Ukrainian, but who also has a father from Afghanistan. So people with these different heritages play a very important role. Vitaliy Kim [for example] has Korean ancestry as well as being a proud Ukrainian patriot. There are many people, and in my other presentations I talk about how diverse Ukraine is today, and those people are all being targeted as well. And so that’s why it really makes sense to talk about Ukraine as a being targeted against the national group of Ukraine, what it means to be Ukrainian.

I do see this as a genocide. I have really argued strongly to be very suspicious of ceasefire, to be very suspicious of pauses to the conflict because like many of us are saying for various reasons that Russia will use this as a chance to regroup. What also is a hard answer from the field of genocide studies is that genocide studies indicate for us that this ends in victory for one side or the other.

And I don’t really want that to be a disempowering answer because I like to remind people that modern Rwanda has its challenges, censorship and a lot of things. But the Rwanda genocide stopped because the military associated with the victim group won. So once the genocide has started, the victim group can win militarily. We’ve seen it in other cases. Often outside interveners play an important role, that’s what we saw in the Holocaust. It’s what we are seeing today. Because again, for this perpetrator ideology that I’m talking about, destruction is the goal here.

I think that Putin really is trying to work towards this world order that he talks about a lot. But Ukraine is center to this very imperial notion about what Russia is and what it has rights over, claims to.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Absolutely. Thank you so much. We have a question that is specifically about the Holodomor from Natalie Pawlenko. So there is still researchers who suggested the Holodomor arose because of rapid Soviet industrialization, the collectivization of agriculture, which you mentioned briefly. Do you think that your research on establishing genocidal intent will substantively change that narrative about the Holodomor? And if not, why not? What are the barriers to really making a fundamental acceptance that this was in fact a genocide?

Dr. Kristina Hook: Great question. I should also mention a few things too. I think that the case of the Holodomor shows how important it is to have people from various disciplinary backgrounds in the social sciences and humanities approaching this case.

The work that I do is really indebted to historians. That’s why I’m so pleased that we just had a question from Roman Serbyn who’s played a very important role in the Holodomor scholarship. Providing the historical, the historiographies, all those details are important for me but then what I bring to the table is this kind of awareness of what I’m looking for. In this case, that’s very consistent with the way that I approach all the cases I’ve ever studied. So I want to point that out for a few reasons. In the work that I do, I’ve really focused on just the year 1932 to 1933 because that’s really seen as the climax of violence. But there were really important famines before and after that other historians also bring to the table. And I will say again that’s not uncommon in the field of genocide studies. A lot of us think about 1994 Rwanda as a hundred days of mass killing, but scholars who study that say that we really should look at 1990 to 1994. So this idea of looking at a climax and then also broadening that scope to those surrounding dynamics is, again, really consistent with the way we approach cases. I don’t know how my research will change that conversation because I think that those surrounding dynamics will be important for people for various reasons, for reconstructing that case.

Genocidal intent should cause people (I would hope with the conversations we’re having in the wider field about decolonizing Russia’s studies) to begin to reevaluate the evidentiary standard for some of the claims that might have worked a couple of decades ago, before we had access to records that we have now, such as explanations of just pure incompetence. I really don’t find that very compelling or persuasive having looked at more recently declassified records myself. So I don’t know if it’ll change all of those wider conversations that you mentioned, but I really do hope that it’ll change this idea that the killing of at least 4 million people according to demographers, which I am not, but the killing of at least that many people in under two years was just some terrible accident. I just don’t find that persuasive.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Frankly from my own position, it seems like the more evidence and the more arguments based on evidence that we have, [the more it] ultimately does a service to the victims of this genocide. And the more we call it a genocide in our own circles and then show the evidence that it was one, that’s really something that we can contribute even if maybe we don’t see the fruits of that in the next few years along the line. As you’ve established this whole field of genocide studies works in conjunction with a lot of others to make sure that definition is agreed on.

Dr. Kristina Hook: If I can just jump in really quickly, I’m also arguing, because the role of oppressions (certainly not in Ukraine where these memories were preserved, but in the wider world) that Stalin nearly got away with this crime because of how much a lack of information led to the kind of flowering of propaganda around it, which we really had to combat. It’s really important for the field of genocide studies to also look at this case. When I’m talking with those colleagues, that’s something I’m arguing about as well.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Absolutely. We have a really interesting question from our audience’s Q&A. Do you know what happened to the Holodomor archives in the temporarily occupied territories? Have you heard of any attempts of Russia, Russian forces there to eliminate them? And I would ask this, not just starting from February but, even back to 2014.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Some of the ways I would talk about the Holodomor to people outside of our Ukraine studies fields, I would say that this is something that might be externally opaque to you, but if you understand this story, you’ll understand the nature of the armed conflict that’s been happening for, eight, or almost nine years, we are about to have a year change.

There was so much sensitivity around this topic on the Russian side. I was thinking today about the screening of Mr. Jones. It was about a year ago that was disrupted by mask men. It was held in Russia. And so even a fictionalized account, which was a very well-done Hollywood production is too much for the society there. When we look today after the February escalation at the destruction of the Holodomor statue in Mariupol. Similar stories that we had in the occupied territories prior to February of this topic being a dangerous topic for Russia because it reminds of Ukraine’s past and present relationship with Russia. It hinted at these darker motivations that I think we’re all horrified to watch come to pass but Ukrainians were well aware of. I put this in my article and I won’t read the full quote, I’d refer you to the Our Life magazine but I spoke with a curator at Holodomor Museum in Kyiv, Yana Hrynko, she says very clearly that she understands that Putin’s encroachment in Donbas and Crimea was not the end of it, that Putin was denying the reality of the Ukrainian state, the Ukrainian identity. She said this in May of 2017. For people willing to listen that the story was really indicating the possibility of what we are just horrifically watching unfold today.

I also realized I forgot to answer the question about archives. I’ll briefly mention that. I have heard about ways to preserve them and I think that all of us who are very concerned about Ukraine’s historical preservation, Ukraine’s cultural heritage destruction that we are trying to watch all of these things. I have heard of people working very hard to preserve these records and digitize things. I try not to comment about them a lot because there’s always this awareness that we want them to be really successful. Sometimes trying to be discreet about what people are doing so that those efforts don’t get disrupted is my motto for now. But yes, people are in Ukraine working very hard to preserve their cultural heritage and we’re all really supportive of that. And I hope that the whole world will be.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: A related question from the audience, from Olenka Krupa, do you think that the scope of this genocide should extend prior to 2014? I don’t know how easy that question is to answer. But I think it’s worth addressing.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thank you to our audience member for that question. That is going to depend on the approach that people take to the case. And I mentioned the shorthand is that there are at least four professionals that bring something to the table for this topic, for the victims, for the world, but do it in slightly different ways. So for me, because I work in perpetrator ideology, I do tend to look at these climaxes of violence.

So I look at 1932-1933 in the Holodomor without at all trying to discount the other historiographies that are broadening that scope. And I would say, probably how historians of the future are going to look at 2014 to 2022. When I’m looking at this case, there’s a database that’s being collected by Just Security at the Columbian Law School. It’s very helpful because it’s keeping track of a lot of hate speech by key leaders in Russian society. And a lot of that language is going back to multiple years before the current escalation. It’s usually after 2014, so how far it goes back? I’m not sure. I will say for legal cases that in a legal case, they’re looking for overlap of two different things: mens rea and actus reus, which means the motivation, the intent and the mind, and the actions. You can think of that as the climax of things where it’s very clear to prosecute the case when those are overlapping. Within scholarship, we tend to look at perpetrators having both the motive and the means, so the abilities. If we look at this hate speech was there an underlying Russian motivation for genocide before the escalation and perhaps they were just constrained in their means for it for various reasons? We’ll have to think about all of these things, but there are going to be various people who broaden the scope out and other people who just look at what I would call the climax without trying in any way to discount the overall dynamics.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: That makes sense. Thank you. Thank you for that answer. I think we have time for one more question. What do you think the future of Holodomor studies looks like and how does Russia’s war against Ukraine affect the progress of future scholarship on the Holodomor?

Dr. Kristina Hook: It is really interesting to watch so many things and historical memory change in real time. Just change before our eyes. So one of my Ukrainian colleagues that I’ve worked a lot with over the last eight years, she and I were discussing it just today. I’m blanking on the title of the song, but she sent me a song which is heavy metal music, and she said “I never expected to see a Ukrainian heavy metal song with images of the Holodomor in it. The song is something about Russia being a terrorist state, we’ll have to find it after. But images in this song, this current song are a reflection of what we are all living through in this moment having these video clips of the Holodomor to talk about long campaigns of Moscow terror against Ukrainians. There’s a tendency of drawing strength from the past, different elements of the past, which can include the Holodomor. But I think we’re also living through a moment that’s going to be studied a lot for the memory of Ukraine. Heroes are being made every day right now in Ukraine. I think Azovstal has a real connotation. The steel plant in Mariupol, which was a last stand for many people, that name of a factory has a real resonance for many of us on the call where before it might have just been a factory.

We’re living through both the transformation of historical memory as well as the making of many of the people who will be heroes for Ukraine of the future. So where it all goes, I’m not sure, but what I do know is that people like you Emily and John, and all of us here, will certainly be there for it.

Dr. Emily Channel-Justice: Thank you. That is just a beautiful sentiment for us to end on and a positive note to close this discussion about some very difficult topics that’s given us a lot to think about. Kristina, thank you so much for your work. Thank you so much for writing this article. And, thanks so much for giving us the time for this conversation.

Dr. Kristina Hook: Thank you, Emily.

Natalie Pawlenko: Thank you both very much for your time this evening and thank you to all our guests for joining us this evening for what was a very interesting conversation. Thank you both to Emily and to Kristina for the work that you do to continue to keep these topics alive and others as well in the scholarly communities as well as elsewhere. Thank you, everyone. Goodnight.